VALVULAR HEART DISEASE

Mitral regurgitation and aortic stenosis are two of the most prevalent valve diseases, affecting millions of patients worldwide. The latest treatment guidelines recommend timely intervention to help ensure better patient outcomes and survival, including transcatheter and surgical options to repair or replace the valve.1

MITRAL REGURGITATION (MR)

MR is the most frequent valve disease in the United States.2,3 Over 4 million people have significant MR, with an annual incidence of 250,000.2-4 Approximately 30,000 of these patients undergo surgery each year in the United States.5 The disease affects millions of people worldwide.

+4M

PEOPLE HAVE

SIGNIFICANT MR

250K

new cases

annually

ONLY

30K

UNDERGO

SURGERY EACH YEAR

1-year mortality up to 57%9

Mitral Regurgitation is a prevalent and progressive disease

MR is the most frequent valve disease in the United States.2,3 If left untreated, MR initiates a cascade of events progressing to heart failure, then death.6-8

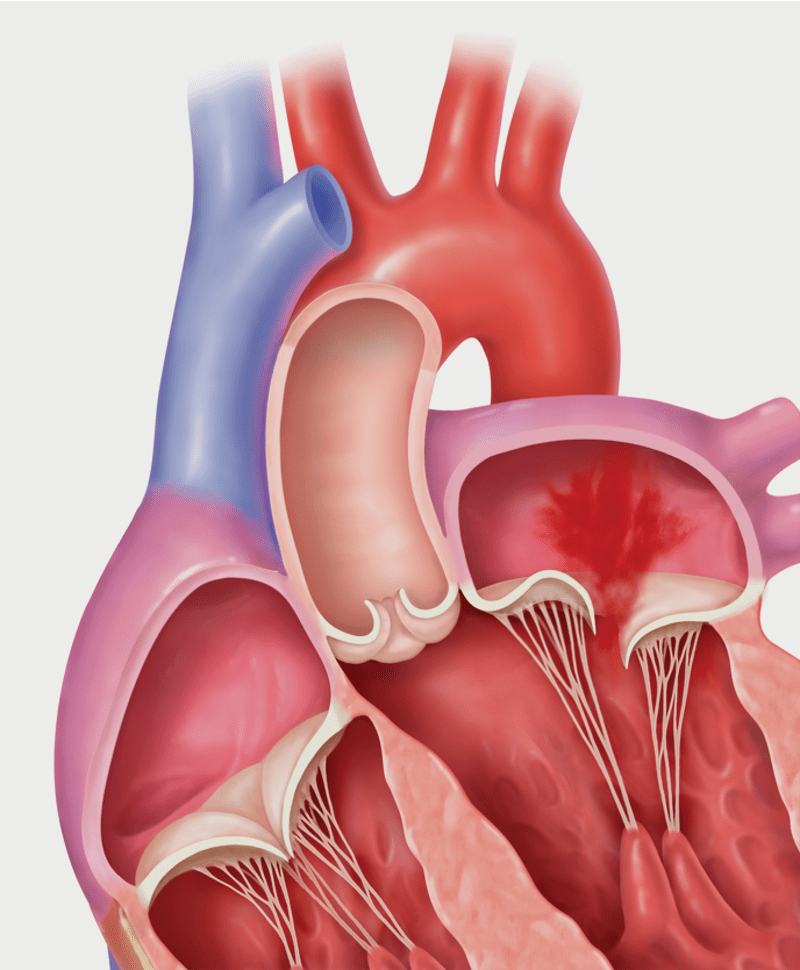

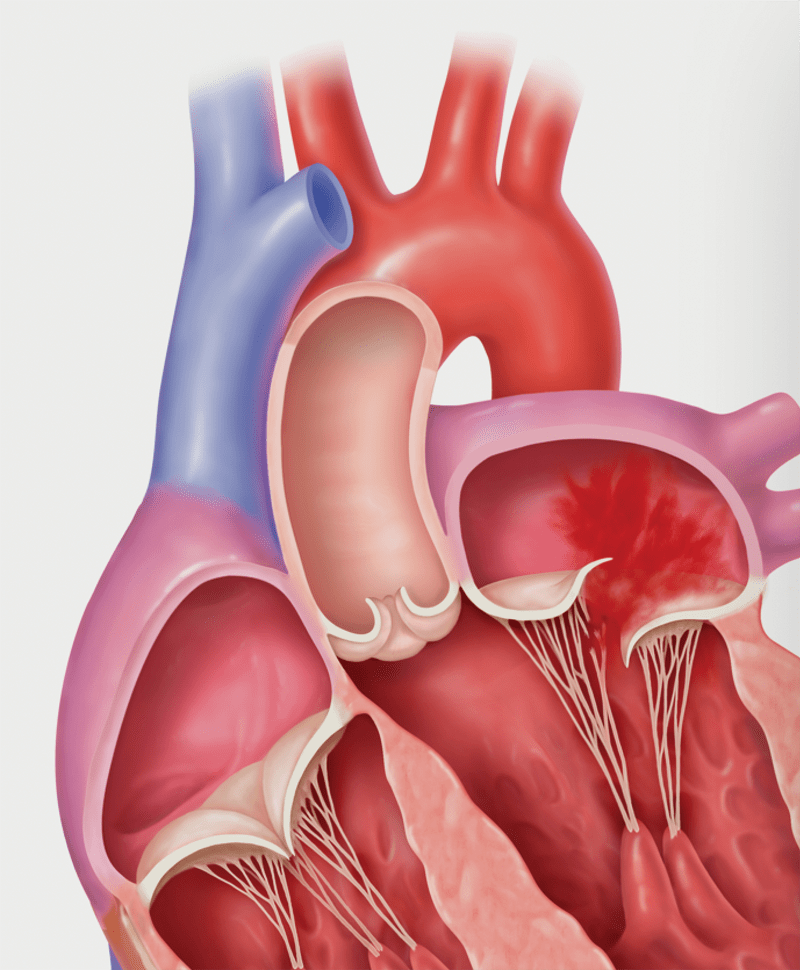

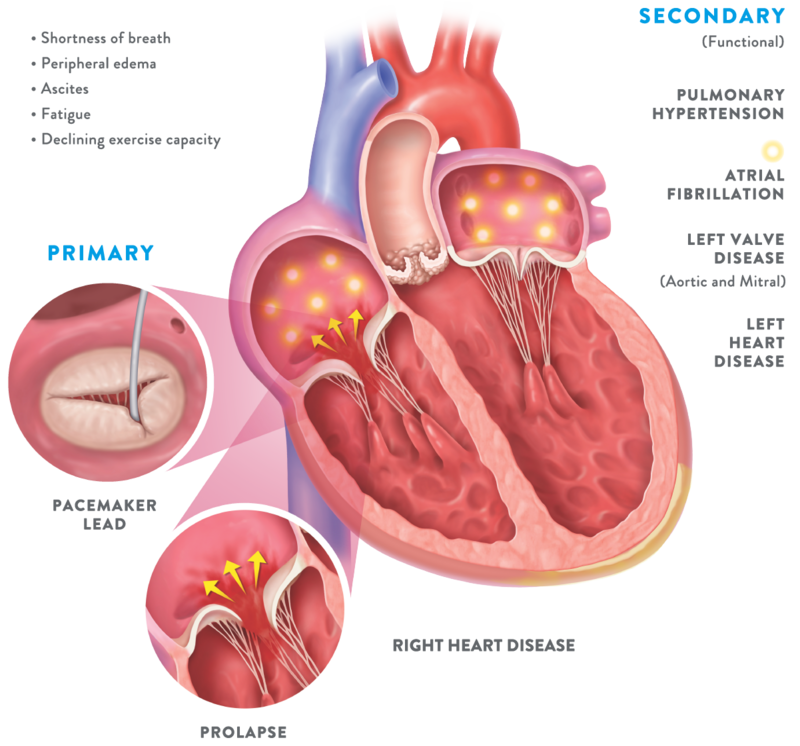

- There are two types of Mitral Regurgitation6

Degenerative MR, also called primary MR, is caused by damage to the mitral valve apparatus with prolapse or flail of the leaflets. It can be related to age, a birth defect, or underlying heart disease. Functional MR, also called secondary MR, is caused by enlargement of the heart due to heart attack or heart failure.

Primary MR (Degenerative MR): Prolapse

Primary MR (Degenerative MR): Flail

Secondary MR (Functional MR)

- Symptoms of Mitral Regurgitation1,12

Symptoms are usually those of heart failure: fatigue, dyspnea, orthopnea, edema, and palpitations.

With left ventricular (LV) enlargement, there is an increase in pulmonary artery pressure and venous pressure, and eventually LV compensation fails.

Auscultation findings include:

- Notable S1

- S3 at the apex, indicating a dilated left ventricle and severe mitral regurgitation

The S3 often suggests a dilated left ventricle and progression to heart failure.

- 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for valvular heart disease include the following key highlights related to Transcatheter Edge-to-Edge Repair (TEER, also known as TMVr) for Mitral Regurgitation1

Currently, MitraClip is the only TEER device approved in the US for treating moderate-to-severe or severe symptomatic MR in following etiologies:

A. Primary Mitral Regurgitation (PMR, formerly Degenerative MR)

- TEER upgraded and is reasonable for treating severely symptomatic patients with PMR, at high or prohibitive surgical risk, mitral valve anatomy suitable for repair and life expectancy ≥ 1 year (Class 2a from Class 2b,

LOE B)

B. Secondary Mitral Regurgitation (SMR, formerly Functional MR)

- TEER is now reasonable in severe secondary MR patients with persistent symptoms despite optimal GDMT* and whose LVEF is 20-50%, LVESD ≤ 70 mm, and systolic PAP ≤ 70 mmHg (Class 2a, LOE B, New).

*Includes sacubitril/valsartan (ARNI, Entresto) and biventricular pacing as indicated.

Note: The 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for management of valvular heart disease deemed TEER may be considered for high risk or inoperable PMR (Class 2b) and reasonable the SMR patients in B above (Class 2a). - TEER upgraded and is reasonable for treating severely symptomatic patients with PMR, at high or prohibitive surgical risk, mitral valve anatomy suitable for repair and life expectancy ≥ 1 year (Class 2a from Class 2b,

“There’s a large population of these patients that are not good surgical candidates. A lot of that age plays a role into, that increases our risk exponentially. One way to remove that risk is through a therapy like MitraClip.”*

Robert Farivar, MD, PhD

Medical Director of Cardiothoracic Surgery

Saint Alphonsus, Boise, Idaho United States

*The testimonials does not provide any indication, guide, warranty or guarantee as to the response patients may have to the treatment or effectiveness of the product or therapy in discussion. Opinions about the treatment discussed can and do vary and are specific to the individual's experience and might not be representative of others.

For many, surgery is contraindicated

and medications are not sufficient

MR patients who most need intervention are often the most likely to be denied surgery.10

Effective intervention is possible for your patients with significant MR

Select patients with significant MR now have more options for effective treatment: not only surgical mitral valve replacement or repair, but transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVr) as well.

EXPLORE MITRAL VALVE SOLUTIONS

AORTIC STENOSIS

The growing prevalence of aortic stenosis and the latest therapy guidelines

Aortic stenosis represents 34% of the native valvular diseases in industrialized nations, and is the most common primary valve disease requiring surgery or transcatheter intervention in Europe and North America.11,12 Of the 146,304 deaths in the U.S. from aortic valve disease (ICD-10 data from 1999 to 2009), 82.7% were from aortic stenosis.2

Due to the aging population, aortic stenosis prevalence is growing: the number of elderly patients with calcific aortic stenosis is projected to more than double by 2050 in both the U.S. and Europe.2

~50%

MORTALITY

AT 2 YEARS

From the onset of symptoms, risk of mortality from aortic valve stenosis is approximately 25% at 1 year and 50% at 2 years if patients, who are already medically treated, do not undergo aortic valve replacement–this is because replacement is the only effective treatment.13,14

>50%

sudden

cardiac deaths

Among this same patient subset, more than 50% of deaths are sudden cardiac deaths, if the obstructed valve remains unrelieved.13 It is theorized that the fatal arrhythmias that precede aortic valve stenosis are secondary to inadequate blood flow through the aortic valve into the coronary arteries.15

~90K

aortic valve

prostheses implanted

Each year, approximately 90,000 aortic valve prostheses are implanted in the U.S. Worldwide, the figure is 280,000, and by 2050 the number is expected to reach 850,000 annually.16

Referrals to cardiovascular specialists

Due to enhanced awareness of various treatments, referring physicians are sending more patients with valve disease, such as aortic stenosis, to cardiovascular specialists, where they can offer patients improved noninvasive imaging tests and greater expertise in interventions. When patients with valve disease are referred for intervention in a timely manner, they can experience better outcomes in terms of preserved ventricular function as well as survival rates.

- Types of aortic stenosis

There are 4 stages of aortic stenosis14:

- Stage A: At risk of stenosis

- Stage B: Progressive stenosis

- Stage C: Severe asymptomatic stenosis

- Stage D: Severe symptomatic stenosis

There is an additional category of “very severe” stenosis based on studies of the natural history of the disease, showing that prognosis becomes poorer as the severity of stenosis increases, and the event-free survival can be 50% at 2 years.

Consequently, patients with asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis require frequent monitoring for progression because symptom onset may be insidious and not well recognized by the patient. An increase in hemodynamic severity is inevitable once even mild stenosis is present.

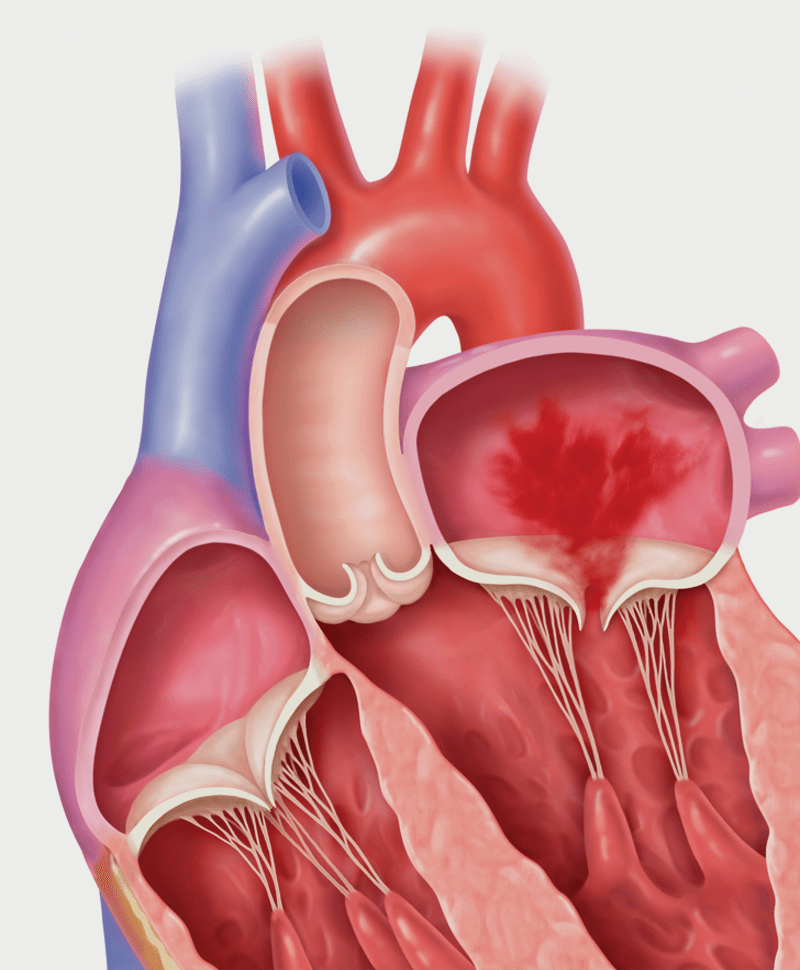

Normal

Mild-to-moderate aortic stenosis

Severe aortic stenosis

- Risk factors

Regarding Stage A, there are certain patient characteristics that reflect risk factors for progression of aortic stenosis, including baseline valve area, degree of valve calcification, older age, history of smoking, and male sex. Other risk factors include presence of bicuspid vs tricuspid involvement, coronary artery disease, mitral annular calcification, hypercholesterolemia, higher body mass index, renal insufficiency, hypercalcemia, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes.2

- Pathophysiology of aortic stenosis

Elevated left ventricular systolic blood pressure accompanies aortic stenosis, yet compensatory mechanisms include LV hypertrophy and atrial augmentation of preload—so cardiac output can be maintained for many years. As the disease worsens, these adaptations become inadequate and the patient may eventually develop symptoms of decreased cardiac output and heart failure.13

- Symptoms of aortic stenosis–signaling need for aortic valve replacement

Due to the often slow, progressive nature of aortic stenosis, patients may not recognize symptoms because they may have gradually limited their daily activity levels. Typical initial symptoms are dyspnea on exertion or decreased exercise tolerance.14

Most patients with aortic stenosis are first diagnosed when cardiac auscultation reveals a systolic murmur; there also tends to be diminished or absent S2. Patient symptoms which are late manifestations of the disease include13:

- Angina pectoris typically upon physical exertion

- Heart failure symptoms such as paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, dyspnea on exertion, and shortness of breath

- Syncope, often upon exertion when systemic vasodilatation in the presence of a fixed forward stroke volume causes the arterial systolic blood pressure to drop

- Systolic hypertension

Symptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis should be re-evaluated at least every 6 months to determine if there is a change in symptoms such as exercise tolerance.12

- 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for valvular heart disease including the following key highlights related to TAVI (previously TAVR)1

A. Symptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis

- Choice of intervention should be a shared decision that considers patient preference, lifetime risks (e.g., long term anticoagulation) and benefits of valve type (mechanical vs bio-prosthetic) and approach (surgery vs transcatheter) (Class I).

- Choice of SAVR vs TAVI bio-prosthesis should be based on symptoms, tolerance for VKA anticoagulation, patient age, life expectancy, approved indication, anatomy suited for transfemoral TAVI, and surgical risk (TAVI vs palliative) (Class I).

B. Asymptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis

- TAVI or SAVR is recommended for those with LVEF<50% whose age ≤ 80 years, and concomitant with other cardiac surgery after consideration by a heart team following recommendation A.1 (Class I).

C. TAVR Valve-in-Valve

- A transcatheter valve-in-valve procedure is reasonable for severely symptomatic patients due to bioprosthetic aortic valve dysfunction (stenosis or regurgitation) and at high or prohibitive surgical risk, and if performed at a comprehensive valve center (Class 2a).

D. Anticoagulation

- VKA is recommended for patients with mechanical SAVR to achieve INR of 2.5 (without thromboembolism risks) or INR 3.0 (with thromboembolism risks) (Class I).

- Single APT for bio-prosthetic SAVR or TAVR patients may be considered in the absence of indications for oral anticoagulation (Class 2a).

- Oral anticoagulation is reasonable up to 6 months for bio-prosthetic SAVR in low bleeding risk patients (Class 2a).

- VKA may be reasonable to achieve INR 1.5-2.0 in patients with On-X AVR and no thromboembolism risks (Class 2b).

E. Diagnosis of valve prosthesis issues

- Multimodality imaging with transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), fluoroscopy, and/or computed tomography (CT) scanning is recommended to detect and characterize valve function, leaflet motion and extent of thrombus if present (Class I).

Intervention: SAVR and TAVR

TAVI (transcatheter aortic valve implantation), also referred to as TAVR (transcatheter aortic valve replacement), is an effective therapy for whom surgery is not an option, as well as an alternative for high-risk patients.17

The strongest indication for intervention is the presence of symptoms. In patients with severe, symptomatic, and calcific aortic stenosis, the only effective treatments include surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) or TAVR—since there is a high risk of death if valve replacement is not performed.14

Even otherwise healthy patients with severe, symptomatic stenosis should nearly always be considered for intervention.6 The choice of proceeding with SAVR vs TAVI is based on multiple factors, including the surgical risk, comorbidities, patient frailty, and patient preferences.1

USE OF TAVI HAS INCREASED MARKEDLY

SINCE ITS APPROVAL IN 2011 WITH

4,627 PROCEDURES

documented in 2012, 34,892 in 2016, and nearly 90,000 total procedures during that time frame.18 TAVI patients are typically older (median age 83 years)18 and at higher procedural risk than those undergoing SAVR—in other words, patients who otherwise may not have received surgical treatment due to their age and risk profile.

DATA FROM THE U.S. REVEALED THAT THE INITIAL LENGTH OF STAY WAS AN AVERAGE OF 4.4 DAYS SHORTER

for patients treated with TAVI compared to SAVR. TAVI also reduced the need for rehabilitation services at discharge and was associated with improved 1-month quality-of-life indicators.2

Medical therapy for aortic stenosis

For aortic stenosis patients, medical therapy alone cannot improve outcomes compared with the natural history of the disease.

Bicuspid aortic valve

Most patients with a bicuspid aortic valve will develop aortic stenosis or aortic regurgitation over their lifetime. In 20%-30% of patients with bicuspid valves, other family members also have bicuspid valve disease and/or a related aortic abnormality. There are no proven drug therapies that have been shown to reduce the rate of progression of aortic dilation in patients with aortopathy associated with bicuspid aortic valve.14

EXPLORE AORTIC VALVE SOLUTIONS

TRICUSPID REGURGITATION (TR)

TR is highly prevalent and undertreated2

In the United States, approximately 1 in 30 people over the age of 65 has significant TR.1 Compared to other valve diseases, TR is one of the most undertreated valvular pathologies, with less than 0.6% of the affected population receiving treatment.2-6

1.6M

TR PATIENTS3

<0.6%

TREATED†

†Calculations performed by Abbott based on: Enriquez-Sarano M, et al. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2019.2

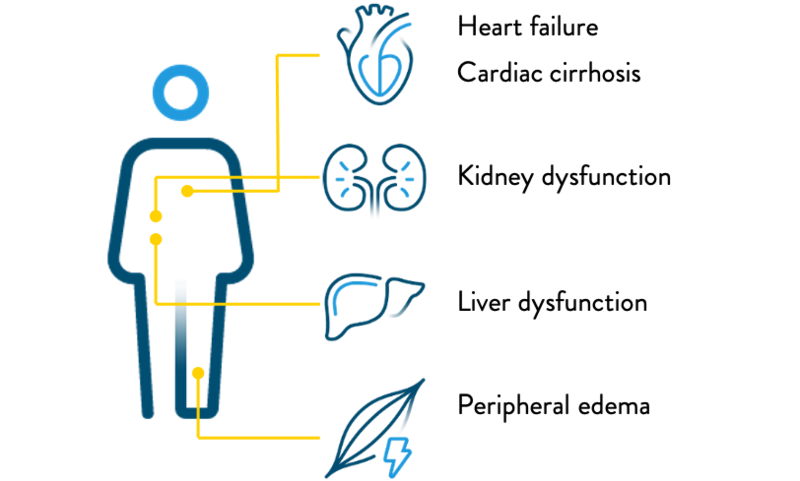

- Severe TR damages other organs, and can lead to multi-organ dysfunction20

- Patients with severe TR have significantly impaired quality of life

Patients with symptomatic, severe TR often experience symptoms such as21:

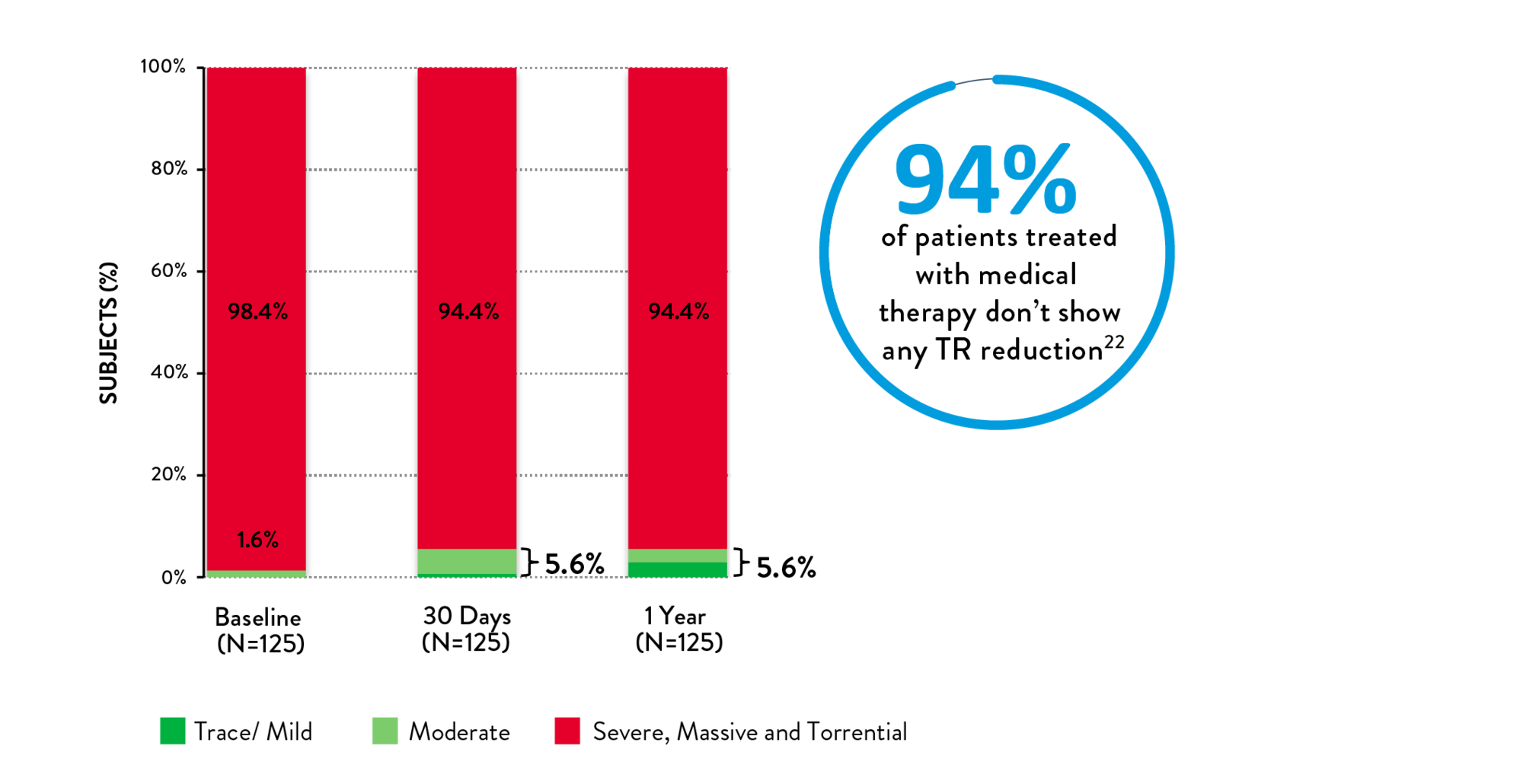

- Medical management for TR has little impact on TR reduction22

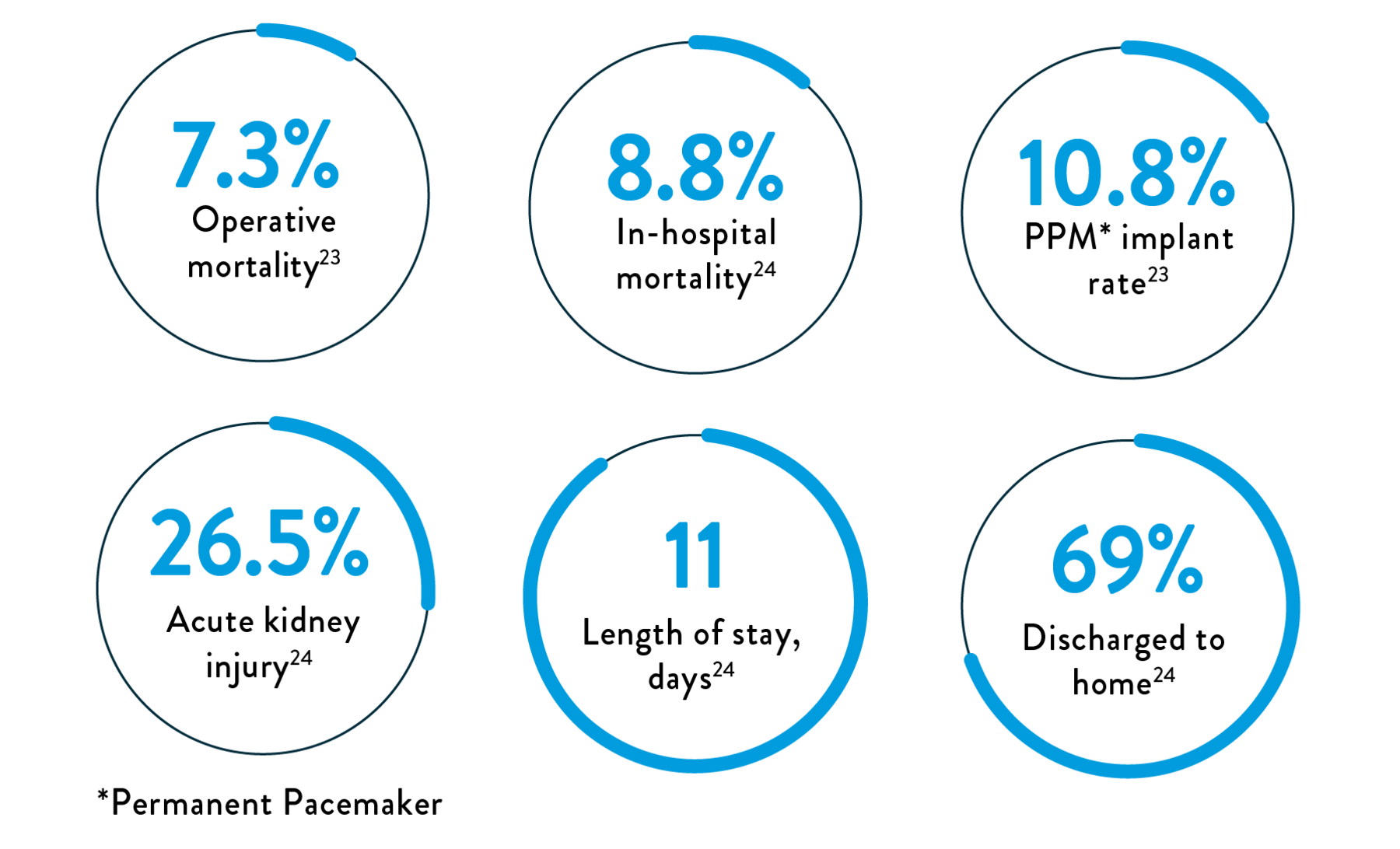

Surgery for TR is rarely performed and is associated with high in-hospital and operative mortality and post-procedure adverse events23,24

Factors prohibiting surgery include:

- Limited clinical evidence25

- High surgical risk (8%–13% operative mortality)25

- Multiple comorbidities25

- Advanced age25

- High rate of adverse events23,24

EXPLORE TRICUSPID VALVE SOLUTIONS

MAT-2201050 v5.0 | Item approved for OUS use only.